Abstract: This article argues that the dynamic growth of the artificial intelligence (AI) sector, supported by an unprecedented wave of investment, bears the hallmarks of a speculative bubble with systemic potential. The analysis shows that the 'AI bubble' could become the first domino in a global financial crisis, exposing decades of monetary pathologies and structural neglect. In 2025, corporate investment in AI reached $252 billion, with forecasts of growth to $7 trillion by 2030. However, the fundamental disconnect between investment expenditure (estimated at $400 billion) and revenue generated (approximately $60 billion), combined with the fact that only 5% of companies achieve a real return on AI implementations, suggests an inevitable correction. The article analyses the mechanisms of circular financing, the role of SPV debt instruments and the expansion of the private credit market as channels for transmitting risk to the wider economy.

Introduction

In public discussions, the threats associated with artificial intelligence (AI) are most often considered from an existential perspective – as a technology that could spiral out of human control or drastically change the labour market. This study proposes a different perspective: AI as a financial catalyst for global economic collapse. This thesis is based on the assumption that the current investment euphoria surrounding generative artificial intelligence.

(GenAI) is a classic speculative bubble, but one that is forming in a uniquely dangerous macroeconomic environment.

The history of financial markets is a history of bubbles – from tulip mania in 1637, through the railway mania of the 1840s, to the dot-com bubble of 2000 and the property bubble of 2008. The mechanism remains unchanged: speculation drives excessive valuations, leading to overproduction and eventual collapse. The specificity of the AI bubble lies in its inextricable link to a decade of unprecedented monetary expansion. The technology sector has been the main beneficiary of the era of "cheap money," which has led to the creation of complex and opaque financing structures.

The article poses the following research questions: Are the current valuations of AI companies justified by economic fundamentals? How do financial engineering mechanisms (circular financing, SPVs) mask the real risk in the sector? What are the potential channels for the transmission of the AI bubble burst to the global financial system and the real economy?

The anatomy of the AI bubble: Analysis of the current situation

Scale of investment

The year 2025 brought record capital flows to the AI sector. According to the Stanford AI Index Report 2025, corporate investment in AI reached USD 252.3 billion, an increase of 44.5% year-on-year. In the third quarter of 2025 alone, $192.7 billion was invested, indicating an acceleration in investment momentum despite warning signs. Market forecasts predict that the total AI market will grow from $279 billion in 2024 to nearly $3.5 trillion in 2033 (CAGR 31.5%) [1]. Infrastructure development is particularly aggressive, with spending on this estimated at USD 400 billion in 2025, with projections reaching USD 7 trillion by the end of the decade.

TABELA 1: Główne strumienie inwestycji AI 2024-2025

| Kategoria | 2024 (mld USD) | 2025 (mld USD) | Wzrost % | Źródło |

| Corporate Investment | 174.6 | 252.3 | +44.5% | Stanford AI Index |

| GenAI VC Investment | 52.5 | 87.0 | +65.0% | EY Report |

| AI Infrastructure Capex | ~280.0 | ~400.0 | +42.8% | Morgan Stanley / Bain |

| Total AI Market Value | 279.0 | N/A | N/A | Grand View Research |

Valuations and market concentration

The market capitalisation of the sector leaders has reached historically unprecedented levels. Nvidia exceeded a valuation of $3 trillion, recording a 300% increase in two years. The so-called "Magnificent Seven" dominated the S&P 500 index, accounting for a disproportionately large share of its gains. Another worrying phenomenon is geographical concentration – 82% of global private investment in AI goes to entities in the US. The case of CoreWeave, whose initial public offering (IPO) in 2025 doubled its share price despite not generating net profits, is a striking example of speculative enthusiasm.

Signs of overheating

Valuation metrics such as price-to-sales (P/S) have significantly exceeded historical norms, even compared to the dot-com bubble peaks. Wharton/UCLA research points to a disconnect between valuations and economic fundamentals, suggesting that the market is pricing in an ideal scenario in which AI instantly transforms every sector of the economy. Sentiment indices, such as the Fear & Greed Index for the technology sector, consistently indicate "extreme greed."

Finansowe domino: Dekady ekspansji monetarnej

Geneza: kryzys 2008 i quantitative easing

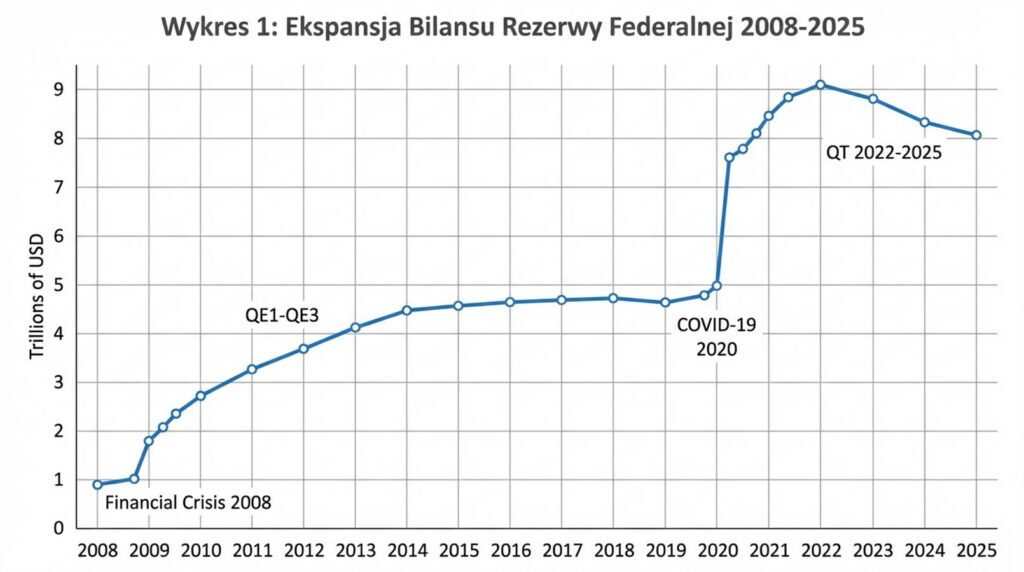

Obecnej bańki AI nie można analizować w oderwaniu od kontekstu makroekonomicznego. Korzenie obecnej sytuacji sięgają kryzysu finansowego z 2008 roku i wdrożenia polityki luzowania ilościowego (QE). Bilans Rezerwy Federalnej USA (Fed) wzrósł z poziomu 900 mld USD w 2008 roku do 4,5 bln USD w 2014 roku, osiągając szczyt 9 bln USD w okresie pandemii COVID-19. Łączna ekspansja bilansów głównych banków centralnych (Fed, EBC, BoJ, PBOC) wyniosła około 25 bilionów dolarów. Polityka zerowych lub ujemnych stóp procentowych (ZIRP/NIRP) wymusiła na inwestorach poszukiwanie zysków w ryzykownych aktywach (tzw. „search for yield”), co skierowało strumień kapitału w stronę sektora technologicznego.

CHART 1: Expansion of the Federal Reserve Balance Sheet (2008–2025)

Visualisation showing the growth of Fed assets from below USD 1 trillion to nearly USD 9 trillion, with phases marked.

Consequences for the financial structure

The prolonged issuance of money led to asset inflation, which for years did not translate into consumer inflation (CPI). A side effect of this was the so-called malinvestments – allocation of capital to projects that would be unprofitable under normal interest rate conditions. A class of "zombie" companies has emerged, kept alive solely by cheap credit. As the Eurodad report notes:

Quantitative easing (QE) has several negative consequences: it fuels wealth inequality, increases systemic risk in the global financial system, and perpetuates an unsustainable debt-based economic model.

Eurodad, 2018

The debt trap

The world is entering the AI era with record debt levels. Global public debt reached $102 trillion in 2024. US public debt exceeds $35 trillion, with a debt-to-GDP ratio of over 130%. Combined with historically high corporate debt, the financial system has become extremely sensitive to interest rate rises, making it impossible to normalise monetary policy without triggering a crisis.

Debt Architecture: Case Study

Nvidia-OpenAI-Microsoft: The financial circle

One of the most worrying phenomena is circular financing. Nvidia has invested USD 100 billion in OpenAI and other entities, which then use these funds to purchase Nvidia chips. Microsoft invests billions in OpenAI, which return to Microsoft in the form of fees for Azure cloud services. Nvidia acquires shares in CoreWeave and guarantees purchases of computing power, which allows CoreWeave to obtain financing for the purchase of... Nvidia chips. This creates the illusion of demand and revenue, which in reality is just a shifting of the same capital within a closed system.

Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) i finansowanie pozabilansowe

Technology companies are increasingly using special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to finance infrastructure off their balance sheets. One example is Meta's $27 billion data centre in Louisiana, financed by private equity firm Blue Owl. The debt incurred by Blue Owl does not weigh on Meta's balance sheet, even though Meta is the sole beneficiary of the infrastructure and the guarantor of demand. This type of financial engineering is reminiscent of the structures used by Enron before its collapse.

The term 'special purpose vehicle' (SPV) gained notoriety around 25 years ago thanks to a company called Enron. The difference is that nowadays companies do not hide this fact. Nevertheless, it is not a foundation on which we should build our future.

Paul Kedrosky, MIT[2]

GPU-secured loans and asset-backed securities

CoreWeave has taken on £14 billion in debt, securing it with its graphics processing units (GPUs). This is a risky mechanism, reminiscent of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) before 2008. The risk lies in the rapid depreciation of the equipment – the launch of a new generation of chips could drastically reduce the value of the collateral, leading to a vicious cycle: a decline in the value of the collateral forces a margin call, which leads to the forced sale of GPUs, a further decline in their prices and more bankruptcies.

Private credit: Shadow banking 2.0

The gap in bank financing has been filled by the unregulated private credit market. Private equity loans to the technology sector are estimated to have reached £450 billion in 2025, with a forecast growth of another £800 billion by 2027. Goldman Sachs reports that the debt of hyperscalers increased by USD 121 billion in one year. The lack of transparency in this market and its links to traditional banks and insurers (which invest in private credit funds) create a significant risk of contagion.

"Unfortunately, it is usually only after a crisis has erupted that we realise how interconnected the various parts of the financial system were."

Natasha Sarin, Yale Law School[3]

The adoption gap: Between hype and reality

- Financial discord

The analysis points to a drastic discrepancy between expenditure and return on investment. With total AI infrastructure spending estimated at $400 billion in 2025, revenue from AI services is estimated at only $60 billion. This gives a ratio of $6.7 in expenditure for every $1 in revenue. OpenAI, despite $20 billion in revenue, generates an annual loss of $15 billion, while planning to spend $1.4 trillion over the decade.

TABLE 2: Revenue vs Capex Gap of Major AI Players (2025 Estimates)

| Entity | Przychody AI (Est.) | AI Capex (Est.) | Ratio (Capex/Rev) |

| OpenAI | $20 mld | ~$35 mld | 1.75x |

| Microsoft (AI segment) | $15 mld | $50 mld+ | 3.33x |

| Sektor AI (Agregat) | $60 mld | $400 mld | 6.67x |

- Verification of adoption in enterprises

A 2025 MIT study reveals a sobering truth: only 5% of companies achieve a measurable impact on their profit and loss (P&L) statements through AI implementations. Although the Wharton study indicates that 75% of companies report improved productivity, these are often pilot effects that are difficult to scale. McKinsey notes that although 78% of companies use AI, only 39% see real benefits in operating profit (EBIT). We are dealing with a "GenAI Divide" – 95% of companies are investing without seeing a return.

- Technical and consumer limitations

Market enthusiasm clashes with physical (energy consumption) and technical (model hallucinations, diminishing returns from scaling) barriers. Nobel laureate Daron Acemoglu warns against overestimating the potential:

"These models are overhyped, and we are investing more in them than we should. I have no doubt that over the next ten years, AI technologies will emerge that add real value and increase productivity, but much of what we are hearing from the industry right now is exaggerated."

Daron Acemoglu, MIT (Nobel Prize winner 2024)[4]

On the consumer side, the adoption of paid AI services is slowing down – according to Menlo Ventures, only 3% of users opt for paid subscriptions.

Historical comparisons: Dot-com vs. AI Bubble

The current situation bears striking similarities to the dot-com bubble at the turn of the millennium. In both cases, we see narratives about revolutionary technology, a “this time is different” mentality, and extreme capital concentration. However, there are key differences that make the AI bubble potentially more dangerous.

TABLE 3: Comparison of key metrics: Dot-Com vs AI Bubble

| Metrics | Dot-Com (1999-2000) | AI Bubble (2024-2025) | Similarity Level |

| Market concentration | High | Extreme (Mag7) | High |

| P/E ratios | Extreme (>100x) | High (30-80x) | Average |

| Debt financing | Low (Equity driven) | High (Private credit, SPV) | Low (AI more risky) |

| Systemic connections | Moderate | High (Banks, Insurers) | Low (AI more dangerous) |

The fundamental difference is the level of leverage. The dot-com bubble was financed mainly with equity (shares); the AI bubble is largely financed with debt, often hidden in off-balance sheet structures. Historically, the bursting of a debt-based bubble has always led to deeper recessions than a stock market correction.

The fundamental difference is the level of leverage. The dot-com bubble was financed mainly with equity (shares); the AI bubble is largely financed with debt, often hidden in off-balance sheet structures. Historically, the bursting of a debt-based bubble has always led to deeper recessions than a stock market correction. and fibre optics."

MIT Technology Review, 2025

Systemic risk: Consequences for the global economy

The bursting of the AI bubble would trigger several crisis transmission mechanisms. First, a stock market crash would hit pension and investment funds heavily exposed to the technology sector (approx. 30% of the S&P 500 weighting). Secondly, stress in the corporate debt market would lead to a wave of bankruptcies among leveraged companies (those using financial leverage). Thirdly, the banking system could be infected through exposure to private credit and a decline in the value of collateral.

Mark Zandi of Moody’s Analytics expresses growing concern:

"A few months ago, I would have said that we were heading for a repeat of the dot-com crash. But all this debt and financial engineering is making me increasingly concerned about a 2008-style scenario."

Mark Zandi, Moody’s Analytics[5]

The effects on the real economy would include mass layoffs in the technology sector (potentially exceeding 500,000 jobs), a freeze on start-up financing, and a decline in tax revenues, which could trigger a sovereign debt crisis in countries with tight budgets.

Collapse scenarios: Crisis mechanisms

The catalyst for the collapse could be one of many events: the bankruptcy of a large data centre operator (e.g. due to the insolvency of a customer such as OpenAI), disappointing quarterly results from Nvidia, or regulatory intervention. The collapse would proceed in four phases:

- Recognition Phase (weeks 1–4): The market begins to price in risk, credit spreads widen, and technology stocks are sold off.

- Infection phase (months 2–6): Private credit funds suspend payments, SPV debt defaults, forced liquidation of GPU collateral.

- Systemic crisis (months 6–18): Problems spread to banks and insurers, a credit crunch hits small businesses, and unemployment rises.

- Consequences (years 2–5): Restructuring of the sector, tightening of regulations, cleansing of the market of zombie companies.

"If the collapse in chip prices is severe enough, a vicious circle could ensue. As older chips lose value, any loan using these chips as collateral suddenly becomes vulnerable to default."

Advait Arun, Center for Public Enterprise[6]

Will the world be fundamentally different after the AI bubble bursts?

Paradoxically, the financial catastrophe caused by AI could heal the foundations of the global economy. It would definitively end the era of "cheap money", forcing monetary discipline and a return to valuations based on real cash flows. It could also lead to the decomposition of technological monopolies and a renaissance of the open source model.

Socially, this crisis would expose the inequalities resulting from bailouts, which could accelerate radical political change and demand for "stakeholder capitalism". Geopolitically, the weakening of the American technology sector could create a window of opportunity for China or Europe to redefine their digital position.

Conclusions

The analysis leads to an unambiguous conclusion: the AI bubble is not just a technological ephemera, but a powerful financial phenomenon with the potential to destroy the global economy. The answer to the question of whether AI is the beginning of the end of the world as we know it is yes. However, this is not a science fiction apocalypse, but the end of an era of financial carefreeness based on the unlimited creation of debt and money.

The scale of the imbalance between investments and revenues, combined with fragile debt architecture (SPV, private credit) and systemic links, makes this crisis potentially more dangerous than the bursting of the dot-com bubble. However, history teaches us that such turning points are necessary to remove systemic pathologies. The world after the AI bubble bursts will be one in which this technology, stripped of financial hype, will finally be able to serve real development, rather than just stock market speculation.

Andrzej Danilkiewicz

Bibliography

- Stanford University Human-Centered AI. (2025). The 2025 AI Index Report.

- Kedrosky, P. (2025). Cytowany w: NPR, „Here’s why concerns about an AI bubble are bigger than ever”.

- Sarin, N. (2025). Cytowana w: Karma, R., „Something Ominous Is Happening in the AI Economy”, The Atlantic.

- Acemoglu, D. (2025). Cytowany w analizach rynkowych MIT.

- Zandi, M. (2025). Wypowiedź dla Moody’s Analytics.

- Arun, A. (2025). Bubble or Nothing: The AI Investment Boom and Financial Stability Risks. Center for Public Enterprise.

- McKinsey & Company. (2025). The state of AI in 2025: Agents, innovation, and transformation.

- International Monetary Fund. (2025). Global Financial Stability Report, October 2025.

- Bain & Company. (2025). Global Technology Report 2025.

- Eurodad. (2018). The politics of quantitative easing.